Behavioral Design

Think Outside The Bias

Published on October 26, 2023

How and when to use cognitive biases in your product design

For many, learning about cognitive biases has become the same as understanding product psychology. For product teams trying to make sense of human behavior, these biases can create a sense of comfort amidst all the complexity. Yet, as comfortable as it may seem, knowing about biases is only the first step, and a ‘Bias focus’ could even hurt your product design. In this article, we’ll dive into the good and bad of cognitive biases with the aim of helping you rethink the way biases are used in practice.

So, if you’re keen to elevate your digital products and truly understand how to design for behavior change, this read is for you.

How biases took over the world

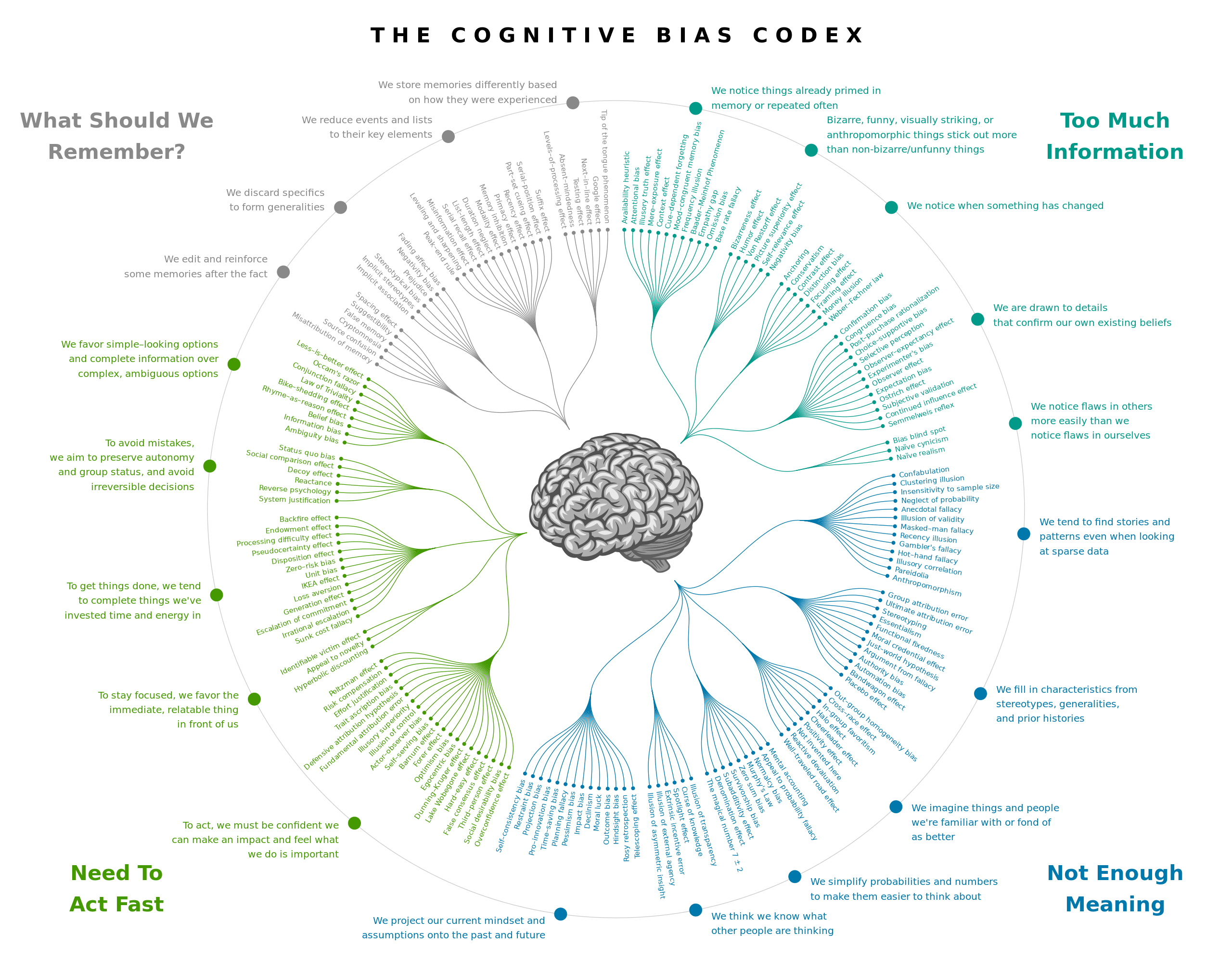

"…observing [visuals like the Cognitive Bias Codex] makes us feel like we are at the cusp of grasping the complexity of human behavior."

Biases, defined as systematic and nearly universal patterns of deviation from rationality, have become widely recognized as part of the reason why decision-making processes go wrong. With catchy names and relatable narratives, biases soon began to transcend the boundaries of academic discussions – bridging the gap between behavioral research and everyday experiences. While they largely originate from single research studies, often tested in labs or limited contexts, they help foster a shared language and understanding of psychological phenomena and seemingly irrational behavioral tendencies. In some cases, a collection of biases, like the cognitive bias codex can be awe-inspiring. Instead of asking who created it or the Codex validity*, just observing it makes us feel like we are at the cusp of grasping the complexity of human behavior.

As biases have gained popularity, they have also found their way into the toolkit of design and product teams. Often employed as checklists, user journey guidelines, or case studies, biases are supposed to offer a sense of structure in the often chaotic landscape of product psychology. In many case studies, ‘bias detectives’ dissect products to identify which biases might be at play or invoked in the designs – essentially labeling design decisions as ‘biases’ post hoc.

"Being able to name and recognize biases does not necessarily equate to understanding their implications in your product or how to design with them in mind."

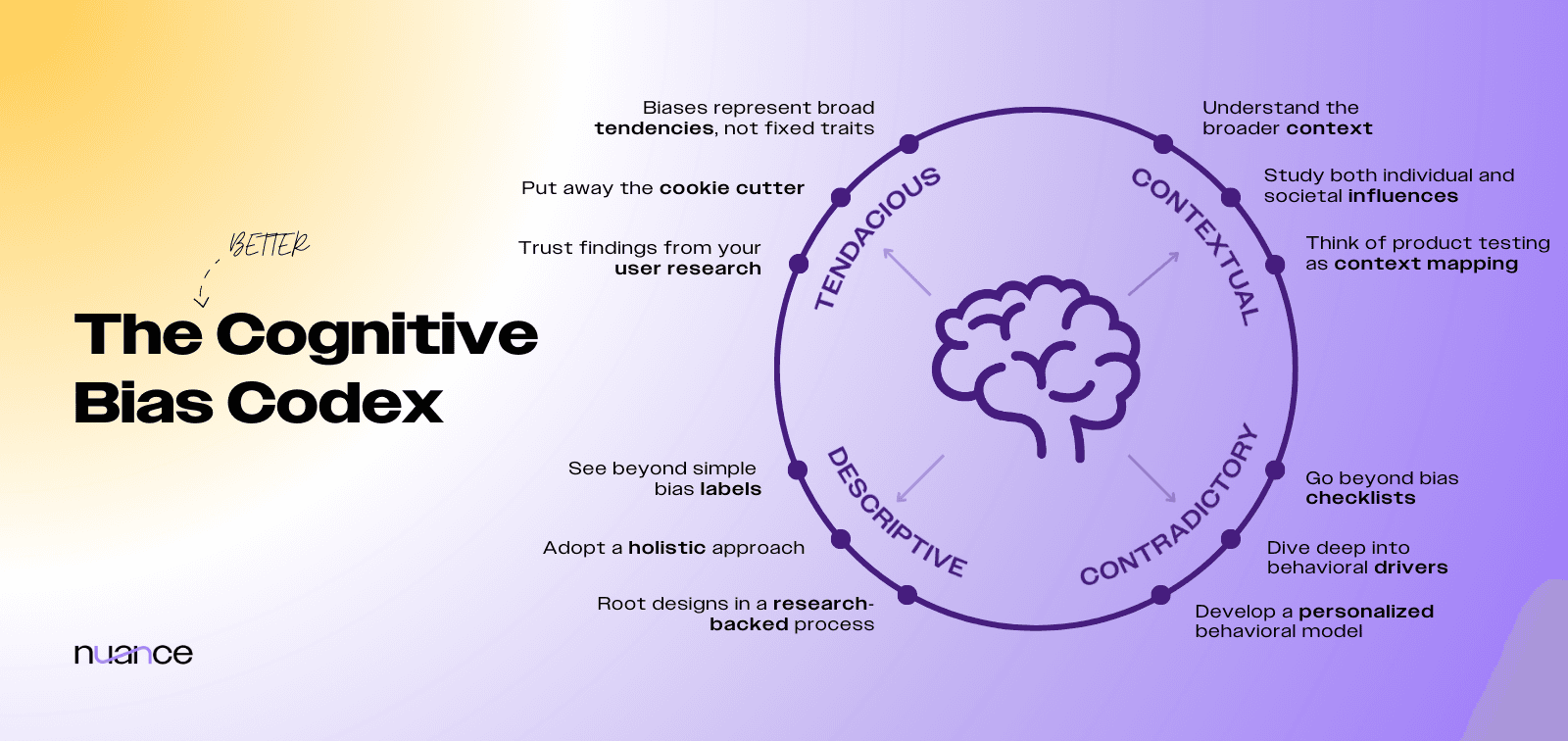

While a fun exercise, it’s easy to question; how valuable are these checklists and bias detectives really? Being able to name and recognize biases does not necessarily equate to understanding their implications in your product or how to design with them in mind. This runs the risk of biases being thrown into product designs without a thorough comprehension of their interplay or contextual nuances. Let’s explore a better approach, starting with a better understanding of cognitive biases.

Is ‘Bias focus’ hurting your product design?

Let’s dive deeper to better understand biases, how not to use them, and some recommended use cases. Let’s see how we can think outside the bias!

1. Biases are tendencies rather than traits

First of all, a ‘bias focus’ fails to acknowledge that biases are broad tendencies rather than fixed behavioral traits that people have. What does this mean? Loss aversion, for instance, is a well-known bias that suggests that the pain of losing something is twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining the same thing. This seems like a clear indicator that people will always be more motivated to avoid losses rather than receive gains. However, is this always the case? Nope! In fact, there is limited evidence for loss aversion, and it’s far from a universal phenomenon. For example, the same person might behave very differently in high-stakes financial situations versus everyday low-stakes decisions. And since individual differences also play a role, some people will naturally be more loss-tolerant, while others might be more loss-averse. The same can be said for most if not all biases.

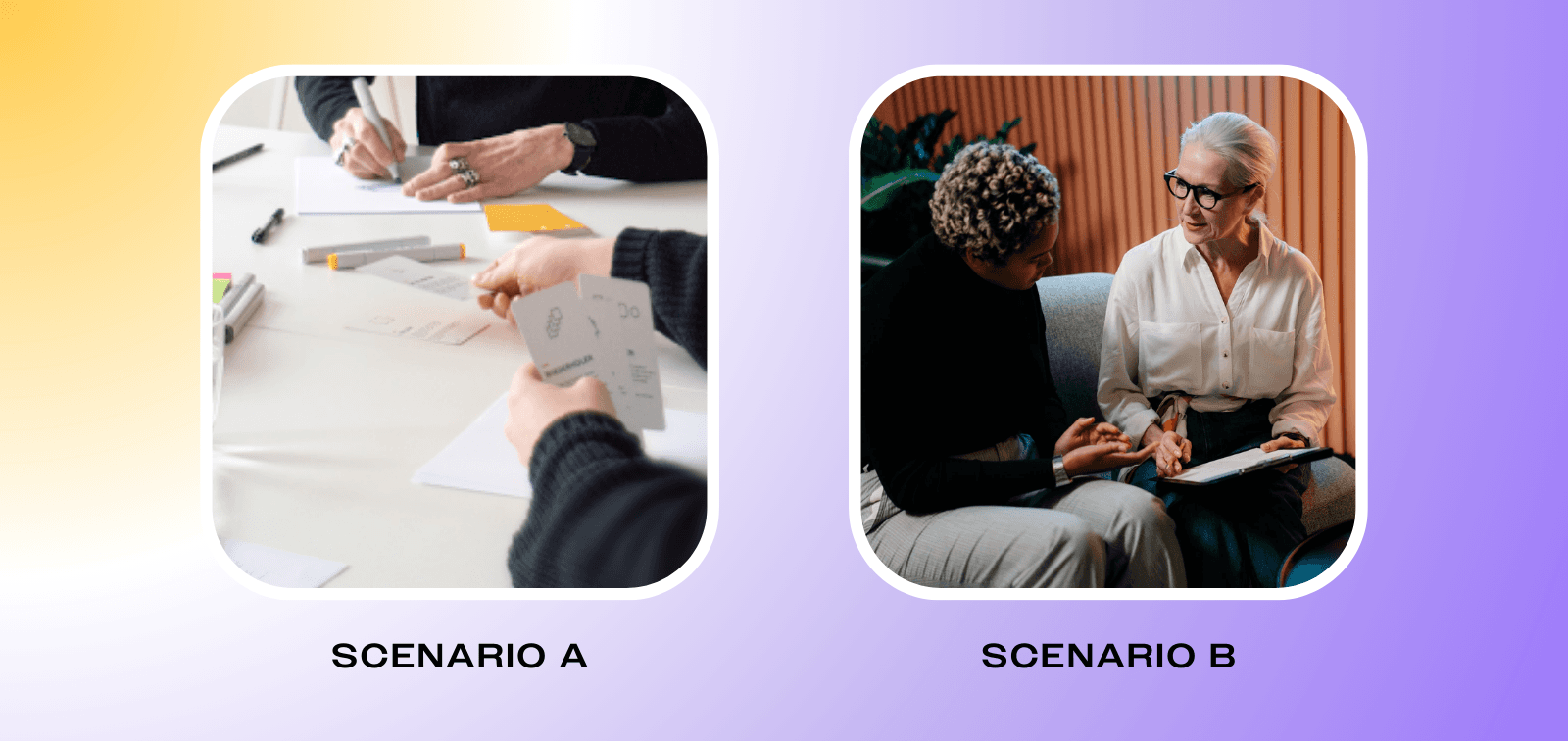

For product teams, let’s take a step back and consider two scenarios of how different levels of understanding this principle can play out in practice with teams facing low user engagement:

Scenario A: The team conducts an ideation session using cognitive bias cards, laying the foundation for a new feature.

Scenario B: Employing user research methods such as interviews, surveys, and literature reviews, the team identifies several cognitive biases within a broader context of user-specific psychological factors. Subsequent usability tests and co-creation sessions guide the development of a new feature.

It’s easy here to see which scenario is likely to achieve the best results. As Scenario A illustrates, designing only for biases assumes a one-size-fits-all approach. But as we all know, behavior is complex. Different people, contexts, and situations require different behavioral interventions. The Scenario B product team understands this and avoid jumping to conclusions.

"By themselves, [biases] tell us nothing about our users."

While biases can offer valuable insights, they should be used as sources of inspiration rather than strict generalizable rules. By themselves, they tell us nothing about our users. And they are not a replacement for thoughtful user research and testing. Always test and validate assumptions in diverse real-world contexts, to ensure that your designs cater to your users.

Recommendations

Recognize that biases are broad tendencies, not fixed traits. Remember that the same bias might not apply universally to all individuals or situations.

Put away the cookie cutter. Designing based on biases will result in a generalized approach, which might not cater to the diversity and complexity of your users' behavior.

Trust findings from your user research. While biases can offer valuable insights, they should come out naturally and not be forced into your user research process.

2. Biases tend to overlook the broader contextual factors that shape behavior

Generally, biases are seen from the point of view of just the individual – recognized as an artifact of their cognition and decision-making alone. Let’s explore how this risks overlooking the broader contextual factors that also shape behavior.

Consider the well-known Marshmallow study, where a child is left alone with a marshmallow and promised a second one if they can refrain from eating the first until the adult returns. The tension mounts as the child grapples with the urge to consume the tantalizing treat in front of them. If children would dig into the first marshmallow without waiting for the second, you could call that a present bias – prioritizing immediate rewards over future and sometimes even bigger ones.

"[The Marshmallow Test] was not a self-control test, but a context test."

For years, the ability to delay gratification in this test was seen as a hallmark of individual self-control, with follow-up studies even linking the ability to delay gratification to greater career success later in life. However, a deeper dive revealed a crucial finding – the substantial influence of the child's home context. Children from unstable, unpredictable environments where promises were not kept consistently were less likely to wait. If you can’t be sure that future promises will be followed through, you take what is in front of you right now. It was not just a self-control test, but also a context test.

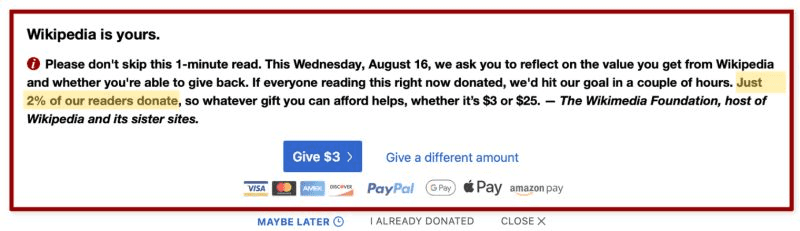

An example of a product team that understood the contextual nature of biases is the team at Wikipedia. In their fundraising campaign, they used social proof in an unexpected way. Instead of emphasizing that a majority of their readers donate, their website banner underscored that only 2% do. This is counterintuitive, as social proof usually suggests that people are likely to copy the majority. To this end, many were quick to criticize Wikipedia for their controversial strategy, thinking they got the concept of social norms wrong. However, Wikipedia's fundraising team hadn’t just gone with their gut feeling; they rigorously tested their strategy. They found that in their context, this approach significantly increased donation rates.

In product design, it’s essential not just to consider biases but also to acknowledge the wider social and contextual influences affecting users. These examples illustrate the same problem as when product teams copy another competitor's successful feature and assume that what worked for others will work for them as well. However, as the marshmallow example taught us, differences in social influences and contexts can lead to very different outcomes.

Recommendations

Understand the broader context. Designing with a sole focus on biases can obscure the larger contextual factors at play.

Acknowledge both individual and societal influences. To effectively design for behavior change, be aware of individual tendencies and the wider socio-cultural and situational factors that shape user decisions.

Think of product testing as context mapping. As Jared Peterson, co-founder of Nuance, notes, “A failed nudge just means that you have more to learn about the context.”

3. Biases simplify the complexity of human behavior into a list of incoherent flaws

Lists of biases simplify human behavior into an incoherent collection of behavioral flaws – deviations from rationally. Consider you are using such a list while creating an onboarding or sign-up process. In this scenario, you have to decide in which order you want to present a handful of options and you want to predict the results. Looking at your list of biases, you quickly face a conundrum: Will most people go for the first option (anchoring or priming)? Or will they choose the last option (recency effect)? Or maybe people choose the option they’re already familiar with (status quo bias), which is opposed to choosing the option that’s new and different (novelty bias). What do you do?

"[Cognitive bias lists are] bundles of mostly unconnected phenomena rather than a cohesive framework."

This thought experiment highlights another big problem with biases; these lists are bundles of mostly unconnected phenomena rather than a cohesive framework. And without a framework, it’s hard to guide the selection of intervention techniques. Instead, you’ll find yourself going through a list of biases, to pick a bunch of ideas and see which ones work best – maybe even contradicting yourself in the process.

What’s more, biases are rarely inherently irrational. Given the vast amount of decisions that we’re making on a day-to-day basis, we’ve developed cognitive shortcuts, or heuristics, to help guide our adaptive decision-making process. Instead of being ineffective decision-makers and victims of many behavioral flaws, we’ve developed cognitive tools that serve us well in unpredictable or complex situations.

Recommendations

Go beyond bias checklists. Relying solely on these can lead to a superficial understanding of behavior, resulting in inconsistent or conflicting design choices.

Dive deep into behavioral drivers. Instead of cherry-picking from a list. Invest in understanding the underlying factors that drive decisions and design your products based on a unified behavioral framework.

If possible, develop a personalized behavioral model. This can guide your design choices and enrich your understanding of the psychological aspects of the user experience.

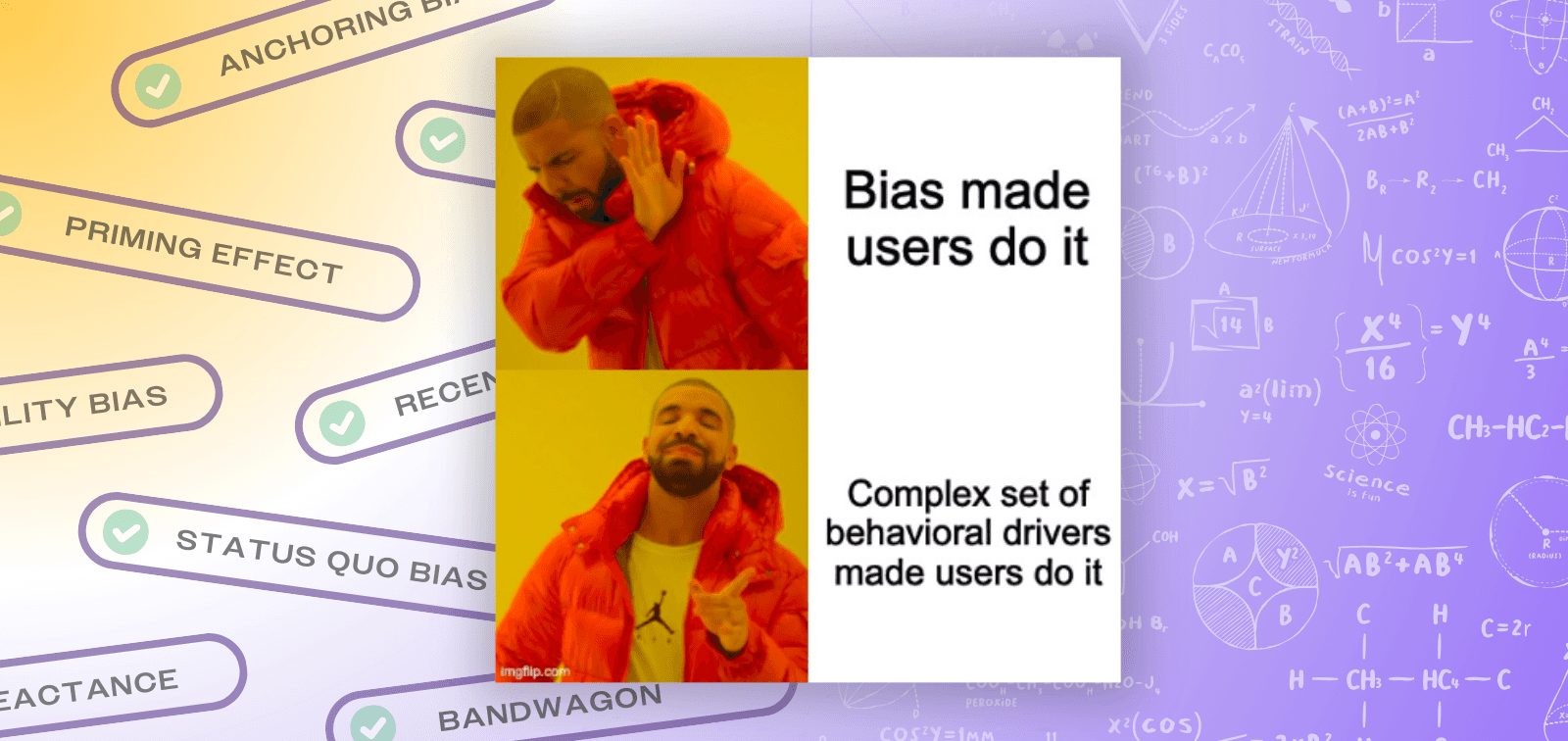

4. Biases don’t really cause behavior, they just describe it

This brings us to a final important issue with biases: biases don’t create an understanding of how human behavior operates in the world. Biases aren’t causing behavior – they’re describing it. Biases are really just labels for deviations from a defined model of behavior.

Take, for instance, a scenario where you are conducting user interviews to analyze user journeys for your fitness center app. You find that several users report going to the fitness center to avoid forfeiting the progress points they have already collected in the app. It might be tempting to immediately attribute this behavior to established biases like loss aversion or the endowment effect, but this merely leads to assigning a bias label to the observed pattern.

When you’re simply analyzing or designing products based on biases, you understand only one facet of the underlying behavior, missing out on the real reason behind people’s actions. Such hasty conclusions can backfire, as they may mask deeper, more complex motivations. You might end up designing features or incentives that aren't resonating with users or are even counterproductive because you're addressing the symptom and not the cause.

In the case of the fitness center app, taking the time to study the insights in more detail you might discover completely different explanations. Perhaps the app has features that allow users to see how they rank among friends or within a community, creating a sense of belonging and making recording progress on it rewarding. This taps into Self-Determination Theory, which focuses on individuals' innate psychological needs, standing in stark contrast to a singular bias-focused perspective. Knowing this, you could foster this fundamental need rather than trying to optimize the best way the points are allocated.

Recommendations

See beyond simple bias labels. While these labels can help describe behavior, they don't uncover the reasons behind such actions.

Adopt a holistic approach to behavioral design. This will help you sidestep the issues that arise from a too-narrow view of human behavior.

Root designs in a good process. Ensure your methods include thorough user research, experimentation, and iterative testing to capture genuine user behavior across different scenarios.

How do we use biases in our work?

Yes, we still use cognitive biases in our work sometimes. That’s right, while it is essential to be aware of the limitations of relying heavily on biases, completely sidelining them isn't the solution either. So, how do we use them? Carefully, selectively, and thoughtfully.

"A good design process also helps to lower the risks of misusing biases."

During a behavioral audit, we sometimes spot areas where considering biases can be useful. Perhaps we’re looking into savings behavior and know there is existing literature specifically focused on biases in financial decisions. The key here is to act wisely – verifying if a particular bias is supported by solid research and if it truly applies to the context at hand. A good design process also helps to lower the risks of misusing biases. If we have already developed a good behavior model or behavioral journey map and understand the context, biases are more likely to help rather than distract.

To sum it up, we aren’t advocating for the elimination of biases from your toolkit. Instead, we emphasize a conscious and informed approach to using them appropriately. We hope that this article has helped you think about biases differently, enabling you to make more thoughtful decisions in your product design.

Recognizing and learning about biases can be a great first step in behavioral design. The next step in developing a true understanding of behavior requires an effective process. With this in mind, it might be worth considering what general behavior change framework is used during your product design to inform your decision-making. In other words, what guides your assumptions and ideas when it comes to designing for behavior change? A good framework should provide a clear, contextually relevant roadmap for your product design and development that clarifies when and how to use biases to achieve the desired impact effectively.

That’s the nuance that will set you apart.

If you would like to learn more about how we design products for behavior change, feel free to reach out via contact.

References

Collins J. (2022, July 21). We don’t have a hundred biases, we have the wrong model. Works in Progress. https://worksinprogress.co/issue/biases-the-wrong-model

Collins, J. (2019, December 19). The case against loss aversion. Jason Collins blog. https://www.jasoncollins.blog/posts/the-case-against-loss-aversion

Davis, A.M. (2018). Biases in Individual Decision-Making. In K. Donohue, E. Katok, & S. Leider. (Eds.), The handbook of behavioral operations ( pp. 151-192). John Wiley & Sons.

Gigerenzer, G., & Selten, R. (2002). Bounded rationality: The adaptive toolbox. MIT Press.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1977). Prospect theory. An analysis of decision making under risk. https://doi.org/10.21236/ada045771

Kidd, C., Palmeri, H., & Aslin, R. N. (2013). Rational snacking: Young children’s decision-making on the marshmallow task is moderated by beliefs about environmental reliability. Cognition, 126(1), 109-114.

Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Rodriguez, M. L. (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244(4907), 933-938.

Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Peake, P. K. (1988). The nature of adolescent competencies predicted by preschool delay of gratification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(4), 687–696. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.4.687

Smets, K. (2018, July 24). There is more to behavioral economics than biases and fallacies. Behavioral Scientist. https://behavioralscientist.org/there-is-more-to-behavioral-science-than-biases-and-fallacies/