Behavioral Design

The Misleading Labels of Behavioral Science – Five Concepts to Better Understand

Published on November 18, 2024

After five years of marriage, I still struggle to explain to my spouse what a "behavioral scientist" does. It's a difficult thing to articulate, and I know other behavioral scientists share this issue. We often rely on terms that oversimplify what we do. If I were to write a description for how Behavioral Science is most often described, this is what I might write: “We apply empirically tested solutions, like nudges, to correct irrational biases and achieve behavior change.”

But is that really what we do?

I worry that the popularity of certain terms has done us a disservice. I wonder if we've allowed good branding to define our field, limiting us in the process.

In the sections below, I’ll offer five unpopular opinions concerning five core concepts—not to discredit Behavioral Science, but to remind us that our field is far more than the concepts that made us popular.

Nudge

"Nudge" is both the best and worst thing to happen to Behavioral Science. It's the best because it helped create our profession, leading to the establishment of behavioral science units worldwide. Without it, I surely would have chosen a different career.

But while "nudge" put our field on the map, it also narrowed the scope of what people imagine Behavioral Science to be. In practice, I’ve never done a project where the goal was to design a single, isolated “nudge” as the term is commonly understood. The effect sizes of these interventions are often too small, and they frequently require costly experimentation due to concerns around generalizability and sustainability.

Instead, most Behavioral Science projects involve shaping the entire context. For example, when working with an exercise app, every stage of the user journey is geared towards developing an exercise habit. Because of this, our goal isn’t to design one "nudge," but rather to create an entire behavioral science strategy that focuses the app on key elements of habit formation. This means we often focus on principles that should be embedded through the entire user journey rather than focusing on a single point of contact. Creating such a framework allows product teams to use their own creativity to design solutions even in the absence of a behavioral scientist.

But this is merely a reason to not describe what I do as “nudging” and not necessarily a reason to abandon the term altogether. After all, developing and testing interventions is still a thing that Behavioral Scientists do–especially in academia. So perhaps while it would be unfair to characterize the field as “nudge,” we can still use the term to describe part of what we do?

I’d say not. The term ‘nudge’ is just not all that meaningful. The traditional definition is ‘any change that influences behavior without restricting options or using significant incentives’. But under this broad definition, almost everything qualifies—from the tone of your voice to the colors you choose to represent your brand. Do we have a coherent definition of nudge that only includes the type of things behavioral scientists do, but not the things that marketers, designers, and every other category of human does when trying to influence behavior?

No, we do not. And I do not believe we would want such a term if it did exist. Why restrict ourselves so?

Were it not for its popularity outside of Behavioral Science, the term “nudge” likely would have been abandoned long ago.

Behavior Change

When I tell people what I do, I often talk about “behavior change.” The term is nearly synonymous with the field – but only “nearly.”

Michael Hallsworth, in his "Behavioral Science Manifesto," argues that while the field initially focused on the discrete measurable outcome of behavior change to prove its value, this emphasis, like the term nudge, has narrowed its scope unnecessarily.

Hallsworth suggests we move beyond describing our field as a toolkit for behavior change, and instead use a different metaphor: Behavioral Science is a lens through which we can understand humans in context. This strikes me as a more accurate metaphor. We research people, frame problems, and develop strategies based on the lens of Behavioral Science. Sometimes that involves the ‘behavior change tool kit’, but sometimes we are there to research, frame, and understand.

Many professions—marketing, sales, HR, operations—aim to change behavior, and they often rely on research to do so. What sets Behavioral Science apart isn’t just our focus on research-informed behavior change, but the unique lens through which we view problems. While other fields often focus on immediate outcomes, Behavioral Science digs deeper, exploring the underlying psychological mechanisms and context-specific factors that drive human action.

In many cases, we’re not just changing behavior; we’re shaping systems, informing strategies, and building frameworks that account for the complexities of human nature. Our role is to ensure that interventions are not only effective in the short term, but sustainable and adaptable across different environments and challenges. This makes Behavioral Science a powerful tool for organizations and teams who need to understand contextual nuances to do their jobs effectively.

Ultimately, our work goes beyond behavior change. It’s about understanding the full picture of human decision-making and providing guidelines, principles, and (occasionally) solutions that respect the intricacies of context, motivation, and cognition. In this way, Behavioral Science isn’t just a toolkit for change—it’s a framework for understanding humans in context.

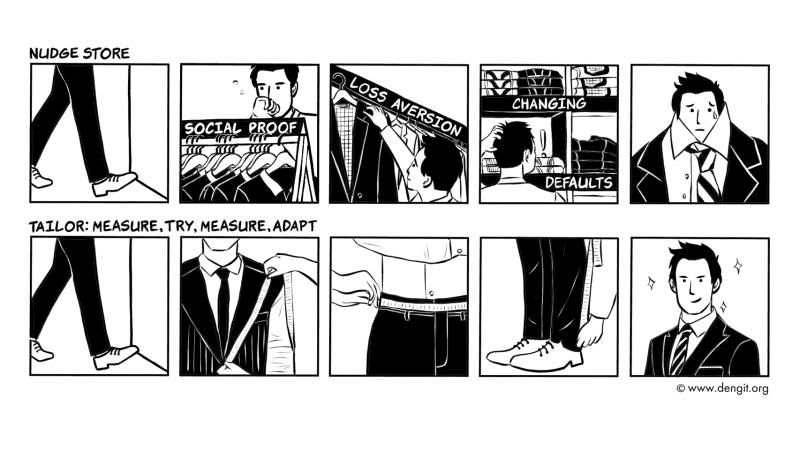

Empirically tested solutions

The phrase “empirically tested solutions” often serves as a rallying cry in Behavioral Science. It’s convincing, reassuring, and scientifically grounded. But here’s the truth: even the most rigorously tested interventions can fail if the context hasn’t been thoroughly understood. The core principle of Behavioral Science is that context matters. Without mapping the specific environment, the success of an intervention in one setting tells us little about its likelihood to succeed elsewhere.

Empirical testing isn’t about proving an intervention’s inherent value. Instead, it tests how well the intervention fits a particular context. For example, if a social norms intervention fails, it doesn’t mean such interventions don’t work—it means something unique in this context disrupted its effectiveness. In other words, the failure reveals a gap in our understanding of the environment, not a flaw in the intervention itself.

This perspective shifts the focus of empirical testing. When we test interventions, we’re really testing our comprehension of the context and problem space. A study’s results, whether successful or not, provide insights into the interplay between intervention and context. This is why cherry-picking “the highest-performing solution” from a list of studies, or the best performing intervention from an RCT or Megatstudy, is rarely enough. Success hinges on how well an intervention aligns with the nuanced dynamics of its new setting.

Empirically tested solutions from other contexts still hold value. They serve as benchmarks and reveal psychological principles that might be relevant. However, these studies don’t offer a universal rank order of effectiveness—they reveal matches between interventions and environments. Behavioral Science isn’t about applying pre-made solutions wholesale; it’s about tailoring interventions to fit the complexities of each unique situation.

Ultimately, the success of any intervention depends on its interaction with the environment. Without a deep understanding of context, even the most “empirically tested” solution is likely to fall flat. Our role isn’t just to test interventions or apply empirically tested solutions—it’s to understand the context and problem with enough detail that we can design for the factors that really matter.

Biases

One day I received an email from Gary Klein who told me he was going to get dinner with Daniel Kahneman, and asked if I had any questions. Knowing Gary had a friendly but adversarial relationship with Kahneman, I saw this as my chance to ask hard hitting questions while I hid safely behind his coattails. Gary would ask the hard questions, and my name would never even need to be mentioned, as Gary would surely be tactful enough to make my questions a little less antagonistic. I hastily wrote 7 questions, none particularly eloquent, and sent them to Gary so that he and I could talk about them before his conversation with Kahneman.

However, the dinner was pleasant, and Gary didn’t want to spoil the mood with my hard-hitting questions. So after the dinner, he simply forwarded my questions. I was mortified. Here is how Kahneman opened up his response email to me:

Hi Jared,

You seem to think that biases are a thing, and that I study that thing and am committed to the existence of biases. If you read a few chapter of ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’, you will find that this description is incorrect.

Nothing like one of your idols telling you that you don’t understand their work.

Kahneman’s claim that biases don’t exist is difficult to explain, but I think of it like this. Imagine someone shoots an arrow at a wall, and that afterwards a judge comes along and paints a target on the wall six inches away from the arrow and says, “Someone is bad at archery. They have a massive bias!”

Is the archer biased? In a sense. They are biased from where the judge thought they should have shot. But is there something called a “bias” that caused the archer to miss the target? Not at all. The bias is a property of how you are measuring, not of the archer.

Similarly, humans use heuristics to make decisions, and Behavioral Economists find that these heuristics systemically deviate–or are biased–from economic models. But is there something called a “bias” which has caused this deviation? No. There is only the heuristic. There is no thing called a bias that is causing anything. The declaration that a heuristic is “biased” is an artifact of what we compare the heuristic against–economic models–not a property of the heuristic itself. Biases describe what heuristics are not–they do not conform to economic rationality–rather than describing fundamental properties of human cognition.

Appreciating that biases don’t exist helps to shift our focus. If you want to understand decision-making, then focus on what people actually do and think, not how those decisions compare to economic models. This was the original intent of Kahneman and Tversky’s work. As Kahneman says in the rest of the email, the goal of studying biases isn’t to understand errors, but to understand human thinking.

What we really try to study are the psychological rules that describe human thinking. We often illustrate these rules of thinking by showing they lead to characteristic mistakes. We do so not because we are interested in mistakes for their own sake, but because correct thinking is the default case, which requires no explanation. This is not a universal rule, but it is often the case that one can learn a lot about a system by examining circumstances in which it fails. For example, memory is studied by looking at forgetting.

All best,

Danny

Recognizing the non-existence of biases challenges us to rethink how we approach our field. Understanding how people choose between heuristics, how heuristics interact, and how they can be leveraged becomes our focus. It’s a shift from viewing people as biased to appreciating the adaptive nature of human decision-making. Which leads into the last unpopular opinion in this article.

Irrational

Given Kahneman’s influence on the field, I hope you don’t mind if I quote him again, this time from a podcast interview:

Kahneman: What I think has happened is that a lot of our work has been misunderstood as an indictment of human cognition. It’s not. One of my least favorite words is the word irrationality. I've never used it…

Greenberg: Is it a mischaracterization …that your work shows that humans are irrational?

Kahneman: Well, absolutely.

Kahneman goes on to clarify in the interview that ‘rational’ is a technical term, as it comes from the phrase “rational actor” in economic theory. This is very different from the definition used in everyday speech. Perhaps instead of interpreting the term “rationality” to mean ‘good decision-making’ we should instead interpret it to mean, ‘thinks like an economist’–which is not necessarily always a good thing. It may not even always be a compliment!

Behavioral Science organizations often focus on “biases” and “irrationality” in their work, but this misinterprets Kahneman’s legacy and distorts the lens through which we view people—as mere sources of error. If Behavioral Science is nothing but a lens to see human error, then it has failed from the start. Such a shallow vision of psychology can never actually fully understand the complexities of human decision making.

Good decision-making often involves heuristics, which are more complex in real-world settings. The Recognition-Primed Decision (RPD) model, for example, shows how experts use heuristics like availability, representativeness, and simulation to make high-quality decisions in fields as varied as firefighting, chess, and aviation. These experts are not using fundamentally different decision-making processes than novices–they still rely on heuristics. Rather, because of the depth of their knowledge, they are able to combine these heuristics in ways that lead to some of the highest quality decision-making that humans are capable of.

Improving decision-making isn’t about replacing flawed processes with “rational” models, but about understanding how these processes lead to good decisions despite their flaws. “Why we succeed may actually be different from the antithesis of why we fail” and so we should be careful when critiquing the decisions that people make, and avoid the label “irrational.”

Conclusion

Nudge. Behavior change. Empirically tested solutions. Bias. Irrationality. These concepts have defined and shaped our field. Between them, they perhaps represent three Nobel prizes—Kahneman and Smith in 2002, Thaler in 2017, and Banerjee, Duflo, and Kremer in 2019.

But I sometimes worry if these successes lure us into complacency. I wonder how much we let good branding and marketing define what we do, and how we do it.

For me, the true strength of Behavioral Science is that it provides a unique lens through which we can research people, frame problems, and develop strategies. It is the science and strategy of understanding humans in context, and it is far from complete or fully developed. We have much work ahead to deepen our understanding of context sensitivity, motivation, and decision-making. Not to mention deepening our understanding of the nuances and intricacies of designing and testing interventions that go beyond the discrete nudges for which the field is known.

It feels wrong to conclude with a definition that might one day limit the field. So instead, I’ll end with a truism: Behavioral Science is what behavioral scientists do. To say much more than that would be to lower my expectations for what the field might become. Perhaps this is bad branding, but I worry that good branding might be an even worse fate.